Business

Week

December 2, 1996

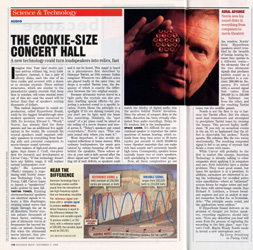

Science & Technology

AUDIO

THE COOKIE-SIZE CONCERT HALL

A new technology could turn loudspeakers into relics, fast

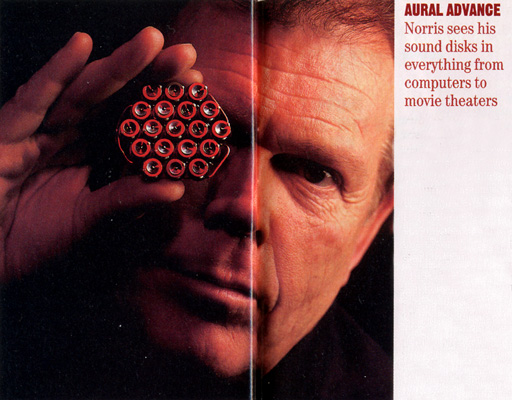

Imagine this: Your next stereo system arrives without big, boxy loudspeakers. Instead, it has a pair of silvery disks, each the size of an Oreo cookie and covered with a dozen or so circular crystals. These curious structures, which are similar to the piezoelectric quartz crystals that keep time in watches, will tease musical notes out of thin air--and the sound will be better than that of speakers costing thousands of dollars.

This radical departure in sound reproduction, called HyperSonic Sound, could be the biggest breakthrough since modern speakers were conceived in 1925. Its inventor, Elwood G. "Woody" Norris, has already filed for three patents and has an additional five applications in the works. He contends his crystal speakers could supplant ordinary speakers in everything from hearing aids and personal computers to movie-theater sound systems.

Some makers of high-end stereo gear agree. Says James J. Croft, vice-president for research and development at Carver Corp.: "If this technology doesn't have any hidden snags, it will replace normal loudspeakers overnight." His Lynnwood (Wash.) company is negotiating with Norris' American TEchnology Corp. in Poway, Calif. Carver hopes to launch a "speakerless" audio system by next fall.

TARTINI TONES. Existing electromechanical speakers use electrical signals to vibrate a thin diaphragm, creating sound waves that ripple through the air in all directions. Norris' crystals pulsate thousands of times faster, emitting a pair of ultrasonic waves at frequencies far beyond human--or animal--hearing. But when the ultrasound waves interact, they produce a third sonic wave--and it can be heard. This magic is based on a phenomenon first described by Giuseppe Tartini, an 18th century Italian composer. Whenever two different notes are played loudly at the same time, out drops a so-called Tartini tone, the frequency of which is exactly the difference between the two original sounds.

Because ultrasonic waves travel in a tight path, the crystals can also produce startling special effects--by projecting a selected sound to a specific location. Norris likes the principle to a spotlight: If it's not shining toward you, you don't see its light until the beam hits something. Similarly, the "spot sound" of a jet plane could be aimed at the ceiling of a movie theater and travel across it. "Today's speakers put sound everywhere," Norris says. "This one puts sound only where you want it."

More important, it also avoids unwanted reflections in home stereos. With ordinary loudspeakers, the music gets tainted by echoes bouncing off the wall behind the speakers. These echoes arrive at your ears a split second after the direct signal and "smear" the sound. Getting rid of such defects, so speakers could match the fidelity of digital audio, was the motive behind Norris' invention. Since the advent of compact disks in the 1980s, distortion has been virtually eliminated from audio recordings. Today, hi-fi's weakest link is the loudspeaker.

SPACE SAVER. It's difficult for any conventional speaker to reproduce the entire spectrum of human hearing, which extends from deep bass notes at 20 hertz (cycles per sound) to shrill 20,000-hz tones. Speaker materials that can make rich bass sounds can't accurately handle high notes. Consequently, speaker boxes typically house two or more speakers, each specializing in narrow tonal ranges.

Now, all these complexities go out the window. Norris' little HyperSonic speakers aren't troubled by the breadth of human hearing because they operate in a different realm--the ultrasonic. One of the two ultrasonic signals that produces audible sound as a byproduct is a constant 200,000-hz frequency. It's mixed with a second signal that varies from 200,020 hz to 220,000 hz. Subtract one from the other, and the resulting Tartini tones run the audible gamut.

Norris is not the first to try to harness the Tartini effect. But the others used dual transducers and attempted to precipitate Tartini tones by crossing the beams. This proved highly inefficient. "If you rely on acoustical events in the air, it's so haphazard that the effect is observable but useless," Norris asserts. His solution: Mix the two waves electronically. The resulting compound signal is fed to an array of crystals that floods a room with music.

While Carver will probably be the first to market this concept, American Technology is already talking to other companies about applying it in computers and cars. Both industries have a similar problem: They want good sound, but space for speakers is at a premium. In addition, carmakers are interested in using the technology for so-called active noise cancellation--where an "antisound" system listens for engine noises and muffles them with mirror-image sounds. Says Richard N. Lehtinen, a former broadcast engineer and now an analyst at market researcher In-Stat Inc. in Scottsdale, Ariz.: "The principle seems sound, and the applications seem endless."

If HyperSonic Sound delivers on its promise of cheaper yet better speakers, recording engineers should take note. "Now, any distortion you hear will come from the process of capturing the recording in the first place," says Carver's Croft. Maybe Woody Norris needs to invent a new microphone next.

By Larry Armstrong in Poway, Calif.

CAPTION:

AURAL ADVANCE

Norris sees his sound disks in everything from computers to movie theaters.

SIDEBAR:

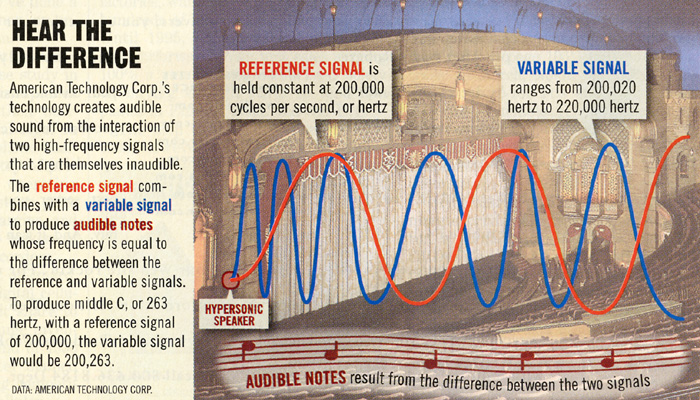

HEAR THE DIFFERENCE

American Technology Corp.'s technology creates audible sound from the interaction of two high-frequency signals that are themselves inaudible. The reference signal combines with a variable signal to produce audible notes whose frequency is equal to the difference between the reference and variable signals. To produce middle C, or 263 hertz, with a reference signal of 200,000, the variable signal would be 200,263.

REFERENCE SIGNAL is held constant at 200,000 cycles per second, or hertz

VARIABLE SIGNAL ranges from 200,020 hertz to 220,000 hertz

HYPERSONIC SPEAKER

AUDIBLE NOTES result from the difference between the two signals.

Contact Webmaster

Copyright © 2001-2005 Woody Norris. All rights

reserved.

Revised: September 29, 2005